Evasive maneuvers require extraordinary courage

One day, a VC friend called me with a request: "Can you help save a startup that’s running out of cash?"

Alongside my M&A work, I work closely with founders as an advisor or investor. We meet as needed — sometimes weekly, sometimes just once a quarter.

This request from the VC was in a more hands-on capacity.

The company was running out of money fast. Revenue growth was crawling. Investors wouldn’t put in more money without a clear change in the company. In the founders' own words, they needed a miracle. They wanted an operating plan to quickly leverage their tech, grow their ARR, and avoid shutting down altogether.

How did it get to this

The founders were all technical and none wanted to run go-to-market. They invested almost all their runway into building the tech but their revenue and user base were very small. There was tech but no product — a product’s value is always in the eye of the paying customer, and, of course, their wallet. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

Development was also rather slow: features with small value impact took months to be implemented.

Finally, there was no formal Board or frequent meetings with investors.

I agreed to help. I would create an aggressive plan (one I would execute if I were the CEO tomorrow) and coach the CEO to execute fast and keep moving forward.

The next two weeks

The plan was "simple":

- Extend runway. Buy the company time. Stretch five months of cash into twelve. Freeze hiring. Cut leadership salaries in half. Terminate the (unused) office lease. Drop underperforming marketing consultants. Gradually restore as ARR increases.

- Prioritize sales. Halt all new feature development. Ship everything built within seven days or shelve it. Everyone—even technical founders—focuses on selling.

- Bring Go-To-Market DNA. Hire an experienced sales/marketing leader, giving them strong equity (junior cofounder level, let's say 8%) with 4-year + milestone vesting.

- Change leadership. Put the GTM founder in charge to reflect the drastic change in company focus and rally everyone behind the new direction.

- Set up governance. Instill accountability. The lead investor gets a Board seat along with an independent member. Track and share key metrics and leading indicators weekly in a shared spreadsheet. Tie leadership equity to revenue milestones.

Simpler said than done, as always.

In the following two weeks, only #1 was implemented.

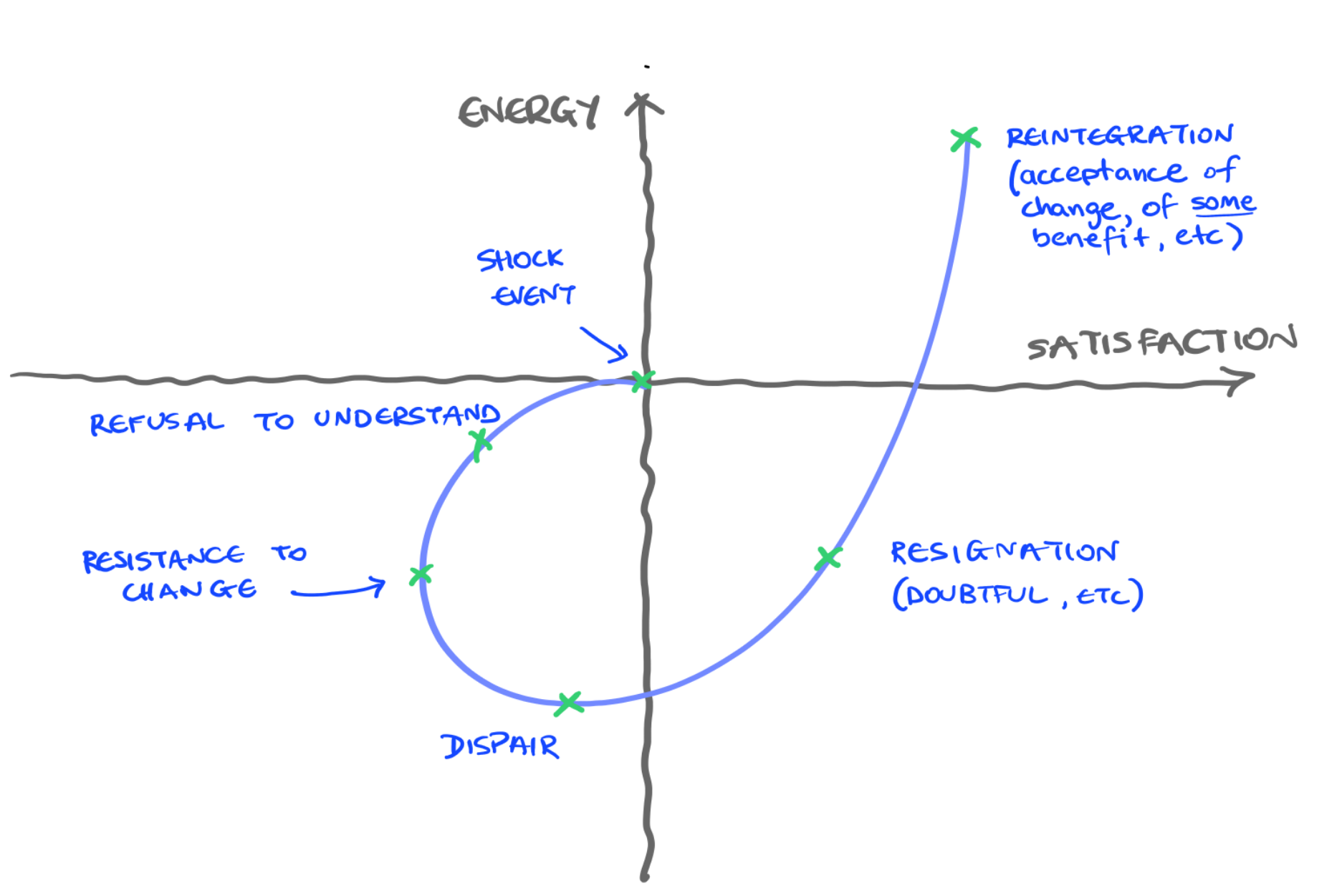

The founders agreed in our meetings that drastic changes were needed, but were hesitant to adopt these ones. They felt the changes I suggested were too extreme and hesitate to make big changes. My coaching failed.

Eventually, the company wasn't able to fundraise and run out of money.

Hard things are hard

I've seen this again and again in my journey as a CEO and with others. Changes like this are always messy, permanent like tattoos, and the harshness and permanence of them will feel wrong no matter what, forcing you to bargain and resist.

The thing is, when your boat is heading toward the rocks, you need a heavy hand on the helm. You don’t just nudge the wheel—you yank it hard. You can’t save a failing company with minor tweaks. If in doubt, move faster, turn harder, make deeper cuts.

Leadership in crisis means making the calls nobody wants to make. Decisive execution is everything. I was once caught in a storm that escalated into 45 mph winds and 3-meter waves. We were three boat lengths from the rocks. Everyone was scared shitless. But with crisp, no-room-for-debate orders from the skipper, everyone helped and we made it out. This is the only kind of leadership that works in dire situations.

Evasive maneuvers require extraordinary courage. As the CEO, you set the tone. While not everyone has the stomach for them, as a leader, you have to grit your teeth and do what the company needs you to do. When Transifex was raising a Series B, we decided to pivot to profitability instead and it almost killed our company. Great people were let go, others resigned. Some investors supported us, some didn't.

But waiting any longer, debating every option, would have been deadly. Your #1 priority as a CEO is to not let the company die.

Advice is just that: Advice

Looking back at this particular startup, I wonder if I should have spent more time making the case for these changes to the CEO—driving home why they weren’t just important, but unavoidable. Maybe it would have made a difference. Maybe not.

At the same time, as an investor or advisor, I keep reminding myself that, the founders are the company. External people can suggest, nudge, encourage, nag and even shout in some cases, but execution isn't on them — it's on the CEO. All you can do is offer your advice. This is especially hard for ex-operators whose instinct is to act and take responsibility. Accept that part of your role is to step aside and let the CEO do their job. The outcome is not your responsibility, it's theirs.

In the end, leaders either act—or they don’t. And that's it. Not much more you can do about it.